Art in Motion: Surrealism

Our Art in Motion series highlights art movements that changed the world. Today’s subject: Surrealism.

In the 1920s, Europe was still recovering from World War I. During the war, under the umbrella of Dada, a group of artists had made an attempt to bring about a social revolution. Rejecting the conventions of logic, reason, and capitalism that had brought about the war, the Dadaists sought to deconstruct these pillars of modern society through sheer nonsense. Dada itself was born as an act of protest and it was through these roots that its legacy would live on, even after the movement itself had lost momentum.

The war had made it clear that there was still a need for societal change, and having sensed that the Dadaists were on to something, a new group of artists were beginning to take up arms to carry on the fight. Rather than attempting to mount their offense through nonsense alone, this new wave, coined as Surrealists by French poet, André Breton, sought to take a more academic approach to their revolution.

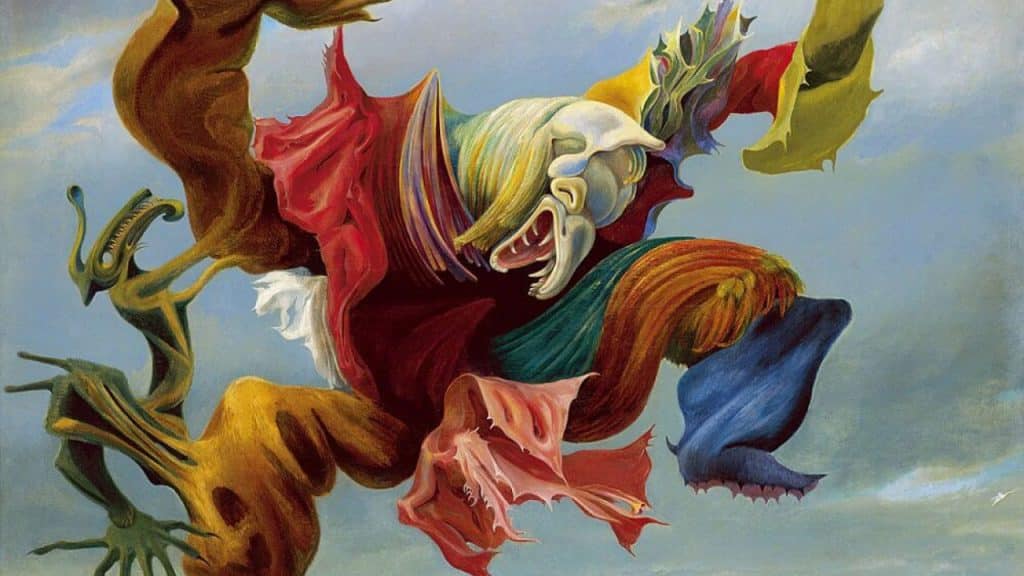

The Eye of Silence, Max Ernst (1943), Fair Use

Breton had experienced the effects war could have upon the psyche during his time as part of the medical staff at a hospital during the war. It was here that two of his worlds would collide. His training in the psychoanalytic techniques developed by Freud along with his creative practice as a writer would intertwine to form the basis for what would later become the philosophy of Surrealism. Following the war’s conclusion, Breton became involved with Dadaism, which would serve as the final key ingredient, prompting the creation of the Surrealist Manifesto, which he would publish in 1924.

The manifesto would outline the basic tenets of the movement, all of which aimed to arrive at purity of thought for the purpose of social change. With the conscious mind being inseparable from reason, morality, and other worldly concerns, the Surrealists believed the unconscious mind to hold the ultimate truth and dedicated themselves to tapping into this resource.

The transfer of information between the unconscious and conscious mind would prove to be a challenge and required an unconventional solution. To effectively mine the contents of their unconscious minds, the Surrealists employed two main tools: automatism and dreams, both of which suppress conscious thought.

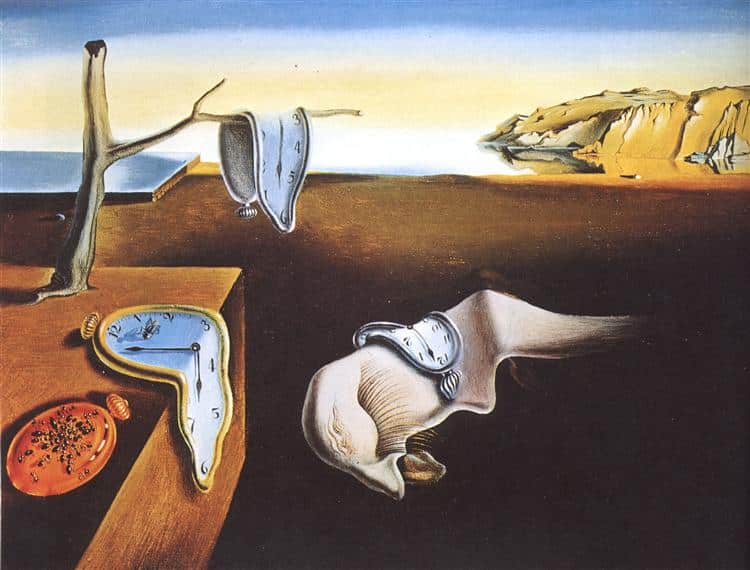

The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dalí (1931), Fair Use

Automatism is the practice of allowing oneself to write or draw freely, without any interference or input from the conscious mind. Essentially, practitioners would set pen to paper and allow their hand to do as it pleased. This technique of chance operation produced spontaneous results and was practiced by both poets and artists, commonly referred to as automatic writing and automatic drawing respectively.

Hypnagogia, the state between sleep and wakefulness, would also prove to be a fruitful resource for the Surrealists. Perhaps the most famous example of which is Dalí, whose surreal paintings are said to be the result of a practice he developed for accessing this state. With heavy eyelids and a spoon in hand, Dalí would take a seat in a chair. As he drifted off into sleep, his grip on the spoon would loosen, until finally, it would drop to the floor where it would crash against a strategically placed plate, snapping him out of his sleep. With the imagery of his dreams still fresh on his mind, he would go to work capturing them on the canvas.

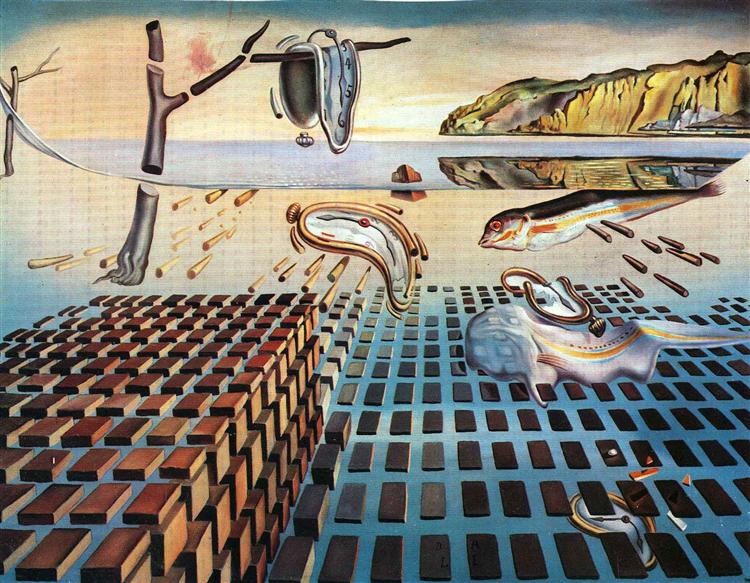

The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dalí (1954), Fair Use

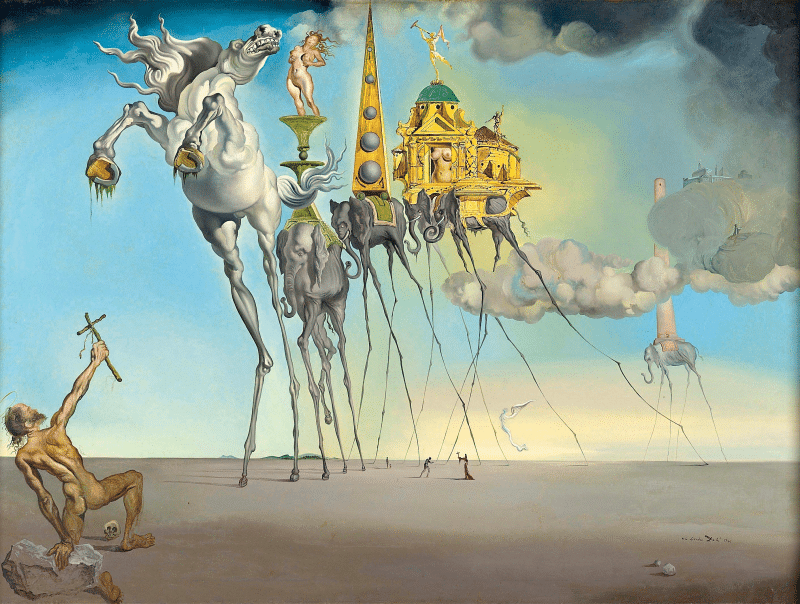

The Surrealists believed that through the juxtaposition of two truths, one could arrive at a new, more emotionally charged truth. This belief is perhaps most evident in the work of Ernst and Dalí, whose paintings often feature distant, yet familiar alien words, existing somewhere on the outskirts of recognition.

Their juxtaposition of the familiar and the alien makes their work strangely relatable and compelling, giving viewers the uncanny sensation of having been to this place or having seen this scene before. This strange sensation is perhaps the result of the artists having tapped into Jung’s theorized collective unconscious—shared experiences common amongst all of humanity.

This would explain why when confronted with the imagery, viewers are struck with a sense of déjà vu. Perhaps this is also why so many of the paintings appear to take place in a similar landscape, despite having been painted by different artists.

The Temptation of St. Anthony, Salvador Dalí (1946), Fair Use

Like Dada, Surrealism had roots in protest. They were nonconformists who believed the tenets of their philosophy to be applicable not only to art, but to life itself, and sought to develop a new way of living. This spirit and the seemingly nonsensical products of the practices are the movement’s strongest link to Dada, and in some ways its natural progression. The surrealists too rejected rationalism—and for similar reasons—though, ultimately, their quest was for truth, and while the journey there often took them through absurdity—absurdity was not the destination itself.

Header image source: The Angel of the home or the Triumph of Surrealism, Max Ernst (1937), Fair Use

Taylor is a concept artist, graphic designer, illustrator, and Design Lead at Weirdsleep, a channel for visual identity and social media content. Read more articles by Taylor.

ENROLL IN AN ONLINE PROGRAM AT SESSIONS COLLEGE: