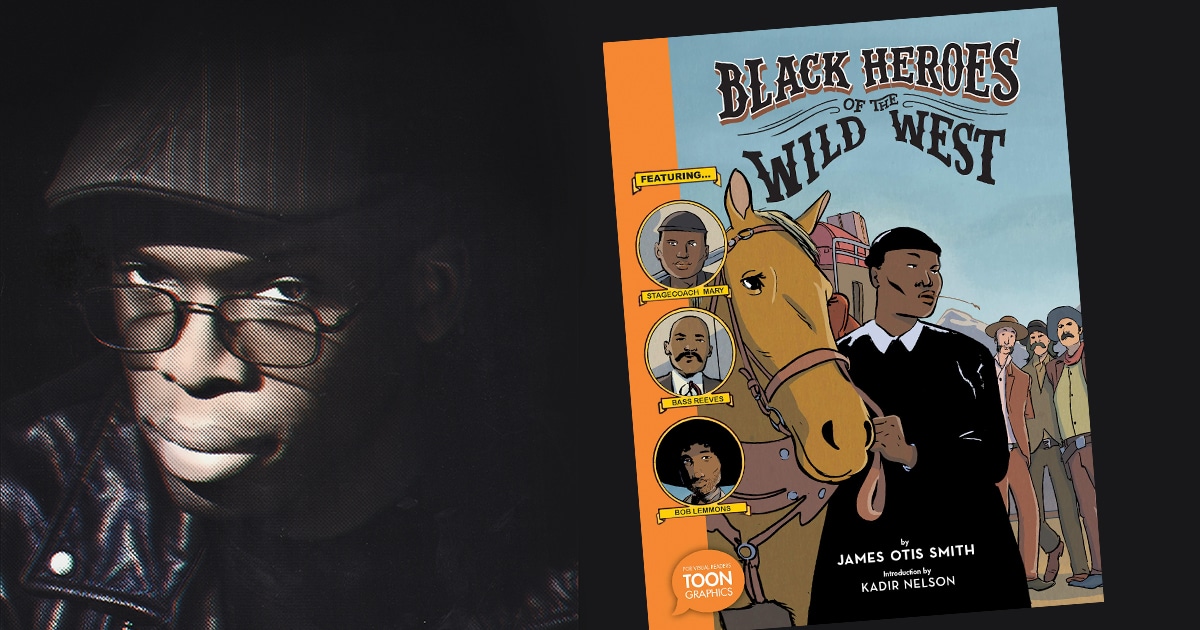

Creating New Heroes for the Wild West

In this interview, James explores how book was developed, discussing books, movies, and video games that inspired him, the challenges of researching and developing stories about real-life characters, and the role graphic novels can play in helping us better connect with our history as it was actually lived.

Q: The last two years must be really exciting time in your career, with the publication of two major works and lots of industry attention, even though COVID has been a major challenge. Has life changed for you?

In terms of work, not really. As a writer and cartoonist I was always kind of a homebody anyway—the biggest change is that I no longer have to come up with excuses for not coming to your party! Before this year, I had only done a couple of book-related appearances. It’s too bad that I can’t actually be out there meeting people, but on the other hand I’ve met more readers and publishers than I would have in person, from even further away, because of video calls.

The biggest negative is not having the occasional studio visit, where I could work in a room with other people. It’s a way to keep your sanity and force you to remember how talk to people. 🙂 Shared studios can also be great ways to network, as people get job offers they can’t take, and they’ll pass them on to you.

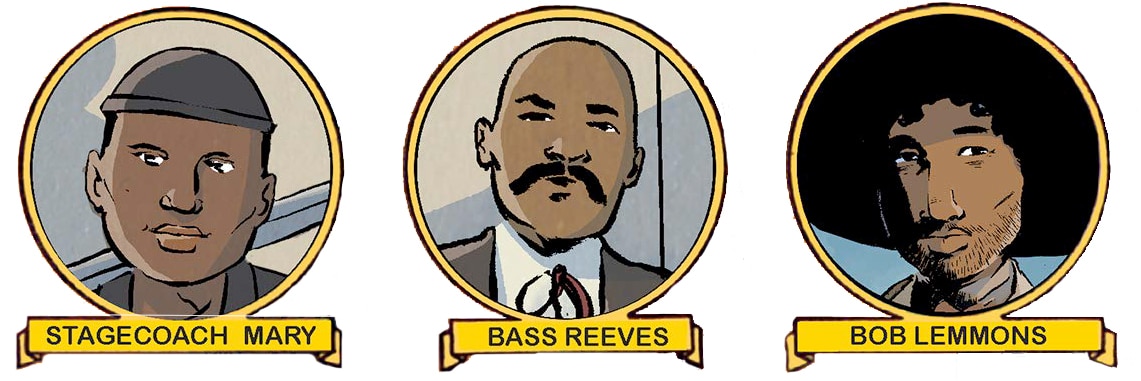

Q: Your book Black Heroes of the Wild West tells the story of three real life heroes (Mary Fields, Bass Reeves, and Bob Lemmons) in epic graphic novel format. Can you talk briefly about their stories and what attracted you to these real life characters?

All three had been born into slavery, and either ran away, like Reeves, or were freed after the Civil War. Mary Fields was a laundress and mail carrier who worked, talked, drank, and fought just as hard or harder than any man; she would be a unique character even today. Bass Reeves ran from bondage, raised a family in Indian Country, and went on to become the first black US Marshall in the west, famous for his integrity and dedication.

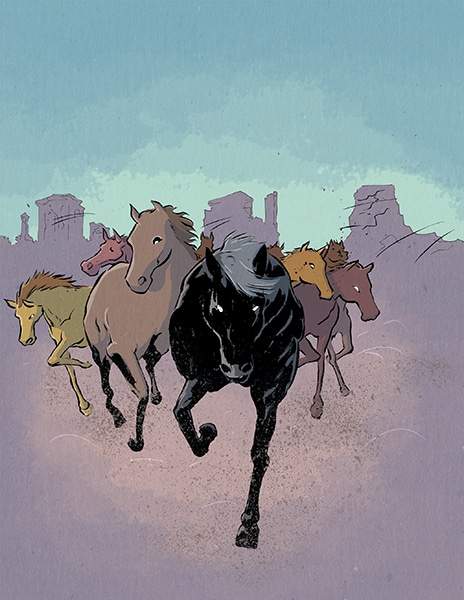

Bob Lemmons developed a humane way to catch wild horses, by spending weeks with them, becoming a part of their herd and leading them back to the corral. This was all during Reconstruction, the period after the Civil War when the southern states were re-integrated into the union. And what I loved about these stories was that they mirrored what was happening with the country itself: these newly freed people were taking the first opportunity life had given them to truly choose who and what they wanted to be. The book is about identity, theirs and the nation’s.

Q: How long did it take you to create the book, from start to finish?

I’ve been collecting information and turning over ideas on stories about the old West for a while, but the actual conversations with my editor and publisher, Francoise Mouly, started in earnest at the beginning of 2019. We started doing specific research on these figures in the Spring of that year, and I finished the art around October. The coloring was done by Frank Reynoso while I was drawing. Frank’s a lot faster than me, so if I had to color it myself, that probably would have taken another month.

Q: What movies or graphic novels about the Wild West (or otherwise) helped inspire or inform your approach to this work?

A major influence was the TV show Deadwood. It was re-watching that which made me realize I hadn’t thought at all about indoor lighting, and that there would in fact be candles everywhere.

Even though I grew up interested in the genre, the Westerns of the 80s were always too slick for me—the actors were too pretty. It wasn’t until Unforgiven in 1992 that I re-discovered my interest.

Old comics like the Marvel westerns from the 50s and 60s, such as Rawhide Kid, Two-Gun Kid, and the old French comic Lucky Luke… The clothes weren’t exactly accurate in those, the stereotypical cowboy hat wasn’t nearly as common as we like to think. But they’re great for atmosphere and visual shorthand. Sometimes just the right silhouette can say everything you need.

Even the videogame Red Dead Redemption was a big help. Because unlike other references, you can actually walk around the spaces and look at things from different angles.

Q: As a creative, you’ve had a diverse career in NYC as a video editor, production artist, set designer, and publisher. When did you first begin creating graphic comic art, and how did your career begin to take off?

I got back into drawing and comics after realizing film wasn’t really for me. I wasn’t done with that business just yet, but I returned to drawing in the early 2000s by way of storyboarding. I drew and colored (but did not write) a children’s book in 2010 while still doing freelance video and graphics, so even though that book never saw the light of day it was the first full book I completed. Once you know you can actually do something, it becomes easier to convince other people that you can do it.

As a freelancer you spend so much time hustling up work you don’t have time to stop and put things in perspective. That’s something you can’t really know when you’re trying to reach a particular stage in your career—actually reaching that stage doesn’t really feel like anything. It’s important to remember to be aware of what’s going on, or you’ll just wind up working straight through your own birthday party.

Just to clarify: that is both a literal and a metaphorical example 🙂

Q: What formal art training or education played a role in your development as an artist? Outside of education, what habits or practices were key to your growth?

I’ve taken life drawing and watercolor classes at various times over the years, but most of my formal education was in film and literature, at Sarah Lawrence College in New York. I still take some life drawing classes whenever I have the time—or at least I did before 2020! As a freelancer, probably the biggest key to my growth is working way too much to the detriment of my own health. (One of the benefits of working on multiple projects at once is that you can use one to procrastinate on the other.) [Editor’s note: I hear ya!]

I’m very big on process. If you’re going to be a commercial artist, you can’t treat art like a mystery—you can’t tell your client that the muse didn’t smile on you today (although definitely take a break when you need one!) So I’ve spent a lot of time figuring out how I work, how I can make this or that stage of the process more efficient.

Treat your process like a machine; break it down and study the parts.

Q: The book is so timely with its exploration of a largely untold history of the West, in which 1/3 of cowboys were Black and just as many were Mexican. What kind of story does the book tell about Black people discovering a chance to create new lives for themselves during the period of Reconstruction and westward expansion?

I want to present, as matter-of-factly as possible, the multiplicity of Black experiences in America. All of these people were enslaved, but once they were free, they had very different ideas about how to move forward with their lives. Bass Reeves became a cop, for the very government that enslaved him. Bob Lemmons would rather spend his time with wild horses than human beings. Obviously, because the book is aimed at young readers, there’s a lot you don’t have the space to discuss, but I hope I can plant the seeds of questions that readers will want to answer as they grow.

Q: How did you gather your research and begin to turn it into stories?

Again, my editor Francoise was a big help here. We both read a lot, and talked about it all. There’s so much background info that doesn’t actually go into the work, but forms the basis of the world I’m writing about. The thing I like about doing non-fiction is that part of your job is that you get to learn something as part of the job.

With fiction, you have much more leeway to collapse things and create composite characters. You use poetic license to change how certain things work in order to amplify the drama. With non-fiction, part of the work is already done in that these events happened; so my job is to then decide where you stop. Mary Fields’ life was so full, it only made sense to cover the whole thing; she really deserves her own book. Whereas every story about Bass Reeves was a little episode about catching this or that outlaw, so I told just one of those stories. And no one was really out there on the plains with Bob Lemmons, they just knew that he showed up after a while with a herd of wild horses.

So the very way these stories have been passed down shaped the different approaches to each chapter. The book becomes less specific and more mythic from start to finish.

Q: From an illustration perspective, how do you approach creating large-scale comic work? For example, do you storyboard each chapter working from a script?

When working with someone else’s script, I’ll put the text into InDesign so I know how much room I have on a page. Then I’ll thumbnail those out, and either scan them to ink digitally, or blow them up to lightbox and ink on paper. Sometimes I try to thumbnail on the computer, but I find I think better when the tools get out of the way, and there’s nothing simpler than pencil on paper. When I’m scripting for myself, I’ll go back and forth between script and thumbnails, but ultimately I’ll wind up with almost the whole book sketched at about 3.75 x 2.5 inches. Figuring out perspective and composition is a lot easier at three inches rather than seventeen.

Here’s a secret to drawing graphic novels: Don’t draw the first page first and the last page last. Start somewhere in the second chapter and get warmed up. When you’re firing on all cylinders, that’s when you go back and do the first and last few pages. Your energy is high, you’ve gotten familiar with the characters, you’re doing your best work and you haven’t gotten burned out yet. So the first and last few pages readers see are hopefully your best.

Q: What else needs to happen in your creative process to really make the work come to life?

This is a dangerous question because you don’t want to get hung up on needing everything to be perfect in order to work. You run the risk of giving yourself an excuse not to work if you don’t have the right incense or Spotify is down and you can’t play your favorite playlist.

But I’ll say this: I’m one of those “messy desk is a sign of genius” people, but the truth is that being able to walk up to the table and just start working is helpful to a degree I can’t quantify. Lower the barriers to work as much as possible, because the human mind is infinitely capable of creating them all on its own.

The upshot here is that cleaning is another great way to procrastinate.

Q: This book is unquestionably going to be a big hit in schools and libraries everywhere. In what ways do you think the graphic novels can make historical content more accessible, for kids and adults?

What started me on this book was the feeling that American history is more complex than we’re taught. We get everything in neat chapters, pass a couple quizzes, and move on to the next chapter. My hope was that in my own small way I could give a young reader the spark to go digging deeper; the realization that what they learned in class or saw on TV wasn’t all of it.

And I didn’t want it to feel like work. I don’t want to sound conspiratorial, but there is certainly a motivation in academic writing to write for other academics, and validate the enormous amount of time and effort one spent becoming knowledgeable enough to write in the first place. Ideally with comics, you’re going in the opposite direction, you’re thinking all the time about how to be more and more clear.

This is something that I stress in the illustration classes that I teach—the need for visual information to be conveyed as clearly as possible, because you’ve really only got a a second or two before the audience moves on. The cliché is that a picture is worth a thousand words, but people don’t treat a picture like a thousand words. We treat it like a single word; we glance at it and move on to the next. If 30 seconds of attention wasn’t worth anything, companies wouldn’t spend millions of dollars on Super Bowl ads every year.

Q: In your career you’ve written for adults and kids, fiction and non-fiction. How do you see your career moving forward? Will you continue to bridge the fiction/non-fiction divide?

I think so. American history can be really depressing! Sometimes you just want to ride a rollercoaster. Also, I have this theory about the way a society normalizes ideas, or people, by making legends of them. We have documentaries about Abraham Lincoln, but we also have movies where he’s hunting vampires. He’s become embedded in our collective psyche. We can make satire and action movie nonsense out of him, as well as multi-part biographies and Oscar-bait and cheap dollar store costumes. Lincoln isn’t going anywhere. I want a wider range of historical figures to get that same treatment.

Q: Any hints you can share about your current or next project?

It’s already been announced so I think I can mention that I’m currently drawing a book on the 15th Amendment for First Second Books. And working on a second book of Black Heroes. And I’m cleaning my desk.

For more information on James Otis Smith, check out his Behance portfolio. For more information on Black Heroes of the Wild West, check out the following resources:

- Black Heroes of the Wild West, Toon Books page

- Book reviews: New York Times, Goodreads, Publisher’s Weekly

- Video interviews with James: Publisher’s Spotlight, Toon Books

Gordon Drummond is the President of a Sessions College. He's passionate about education, technology, and the arts, and likes to surround himself with talented people. Read more articles by Gordon.

RECENTLY ON CAMPUS