Art in Motion: Pop Art

Our Art in Motion series highlights art movements that changed the world. Today’s subject: Pop Art.

In the 1940s, the world was breathing a collective sigh of relief at having finally reached the conclusion of the second world war. With much of Europe still in the midst of reconstruction, the international art scene’s focus shifted its attention to New York, where a new movement was beginning to take shape.

Many prominent figures and practitioners of European Modernism had fled to the United States during the conflict, many finding refuge in universities, where they would take up positions as professors. This influx of European influence had a profound effect on the following generations of American artists, who would, for the first time, place America at the forefront of the art world. The Abstract Expressionists sought authenticity through the exploration of the self, believing spontaneity and improvisation to be a means of tapping into the unconscious.

As is always the case, the next generation of American artists to make a wave would adopt a set of values in direct opposition to the Abstract Expressionists who had come before them. Beginning in the late 50s, a new movement was born in both the United Kingdom and the United States. Pop Art, as it would come to be known, was a bold, graphic, rejection of the self-indulgent musings of the Abstract Expressionists.

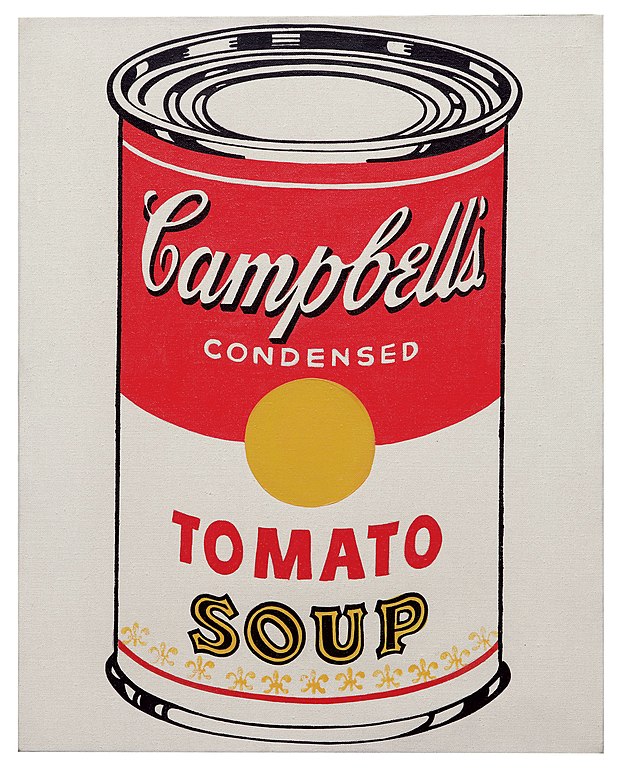

As the name suggests, a main tenet of Pop Art was its prolific use of pop culture imagery. Pop culture being commercial in nature, this usage extended from mass-produced goods down to the ads used to sell them. As did the subject matter from which it pulled inspiration, Pop Art aimed to reach everyone, serving to democratize art by shifting the narrative from cerebral and relatable, to simply recognizable.

Campbell’s Soup Can by Warhol 1962, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Gone were the loose, conceptual whispers that evaporated into the ether before escaping vagueness, and in their place was crisp, bold, logo-emblazoned substance. Pop Art’s lack of personal subject matter made the art more accessible to larger audiences and its clarity made it easy to understand. The fact that people could participate through recognition alone gave the movement great mass appeal and the potential for widespread popularity.

This usage of everyday, commercial objects as the subject matter for Pop Art was a response to the perceived incompatibility of traditional fine art subject matter with modern life at that time. Like many movements, this sentiment was born from the lack of a sense of connection to the works hanging on museum walls and studied in school. For the burgeoning Pop Art movement, advertisements and mass-produced goods were much more reflective of their world than the works of Rembrandt.

By elevating the mundane to high art, the Pop Artists challenged the traditional notions of status not only in regard to subject matter but to fine art itself. This stance echoed the position championed by Marcel Duchamp, albeit without any novel conceptual contribution. In fact, what was intended to be a response to the subjectivity of Abstract Expressionism might also be viewed as the next logical step in its evolution—with Pop Art serving as an exploration of the collective unconsciousness and the effects of pop culture upon it.

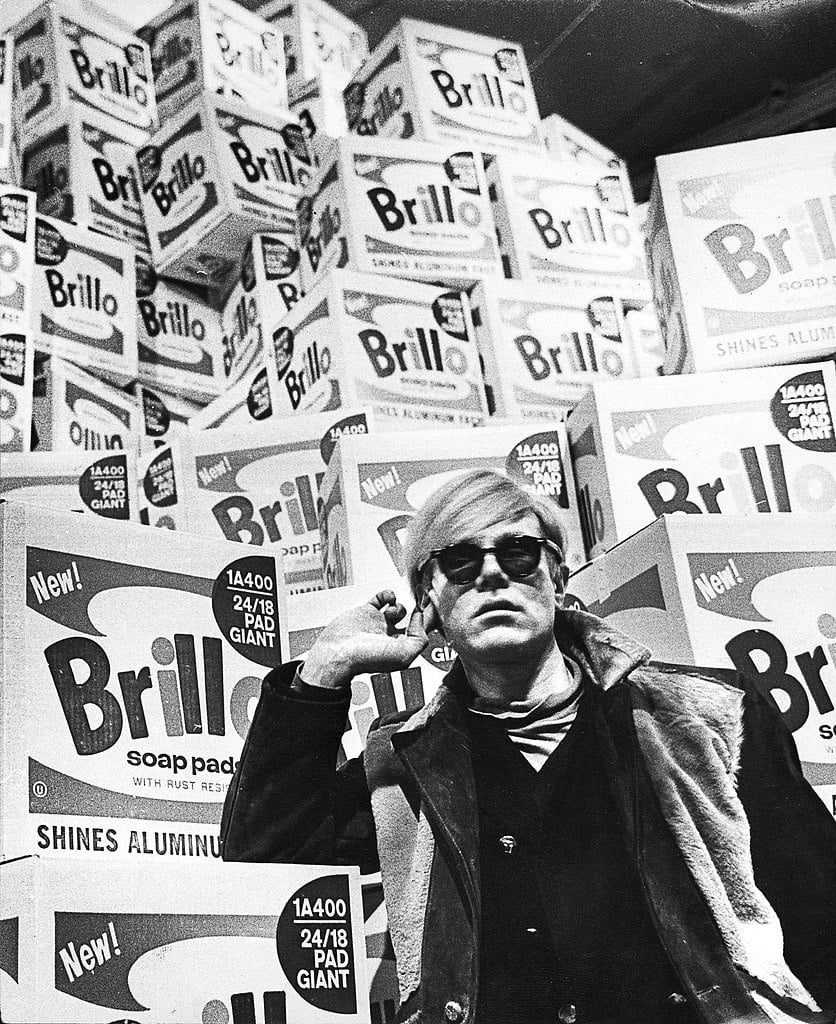

Andy Warhol in Stockholm 1968, Lasse Olsson / Pressens bild, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

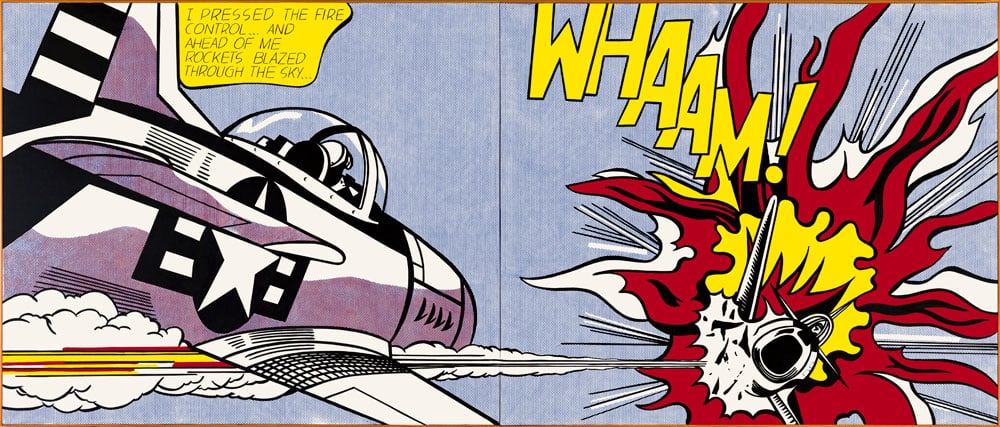

The ways in which Pop Art would distinguish itself from Abstract Expressionism would extend beyond just subject matter and into technique. The loose, expressive brushwork and improvised compositions of the Abstract Expressionists were replaced with the calculated precision and hard edges found in printed subject matter like advertisements, comics, and packaging that the new movement sought to emulate.

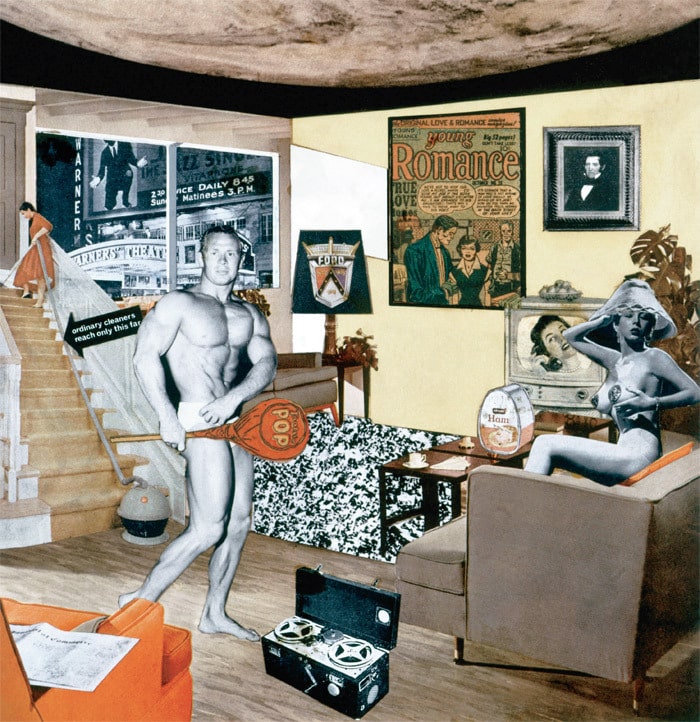

These traits were mostly found in the American art produced during this time, with the British portion making ready use of collage. While the movement’s origins may have shared similar roots, the cultural differences between the United States and the United Kingdom lead to the development of two divergent interpretations of Pop Art.

While today both movements share a name, they had a markedly different point of view. Whereas much of what was created under the umbrella of pop art in the United States was created in earnest, across the pond, the practitioners of pop art took a much more tongue-in-cheek approach.

American Pop Art can be seen as the embrace or celebration of pop culture—a unification of sorts between high and low-brow art, whereas in the UK, the movement adopted a more critical lens—examining the implications of pop culture, and in particular, of advertising, upon our way of life. To this end, the UK practitioners, spearheaded by the Independent Group in London, while also making use of parody and humor like their American counterparts, attempted to provide some form of commentary on the culture rather than to simply draw attention to its existence.

One interesting example of the contrast between the two movements is The American Supermarket, an exhibition held at the Bianchini Gallery in 1964. The show gathered a team of international Pop Art practitioners to transform the gallery space from the typical white wall affair into a functional supermarket, with one key difference—all of the items in its inventory had been created by artists. Visitors were invited to browse and purchase from the market’s offerings which included paper bags by Warhol, chrome eggs by Watts, and wax donuts by Inman.

The point of this juxtaposition seemed to be just celebration of the mundane as art, and it was perhaps this celebratory nature of the American variant of the movement that resulted in wider public acceptance and greater success than its counterpart across the pond. The recognition of the subject matter and the simple and pure embrace of its culture, rather than any form of critique or examination, made the movement more accessible to the public, something everyone could participate in.

The movement produced some of the largest names of the century in regard to American art. Artists like Warhol and Lichtenstein ascended to celebrity status and enjoyed widespread fame during their careers. Due to the commercial nature of their work, Pop Art pieces are easily reproducible, which has resulted in their becoming a ubiquitous part of Americana, remaining some of the most recognizable art to this day. Pieces from this era can often be found adorning the walls of American restaurants and just about any form of merchandise you can imagine from t-shirts and tote bags to shower curtains and shoes.

Header image: Roy Lichtensetin (1967), Eric Koch, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Taylor is a concept artist, graphic designer, illustrator, and Design Lead at Weirdsleep, a channel for visual identity and social media content. Read more articles by Taylor.

ENROLL IN AN ONLINE PROGRAM AT SESSIONS COLLEGE: