Art in Motion: Symbolism

Our Art in Motion series highlights art movements that changed the world. Today’s subject: Symbolism.

Toward the tail end of the 19th century, a group of writers and visual artists were growing disillusioned with the state of things around them. Perceiving the decline in spirituality of modern life to stem from rationalism and materialism, this new group turned their attention inwards.

Beginning with the rejection of the literary movement of Naturalism, and followed by that of Realism in painting, a new wave of writers and visual artists that would come to be known as the Symbolists, championed imagination over reason, holding their subjective truths over that which could be found externally in the observable world.

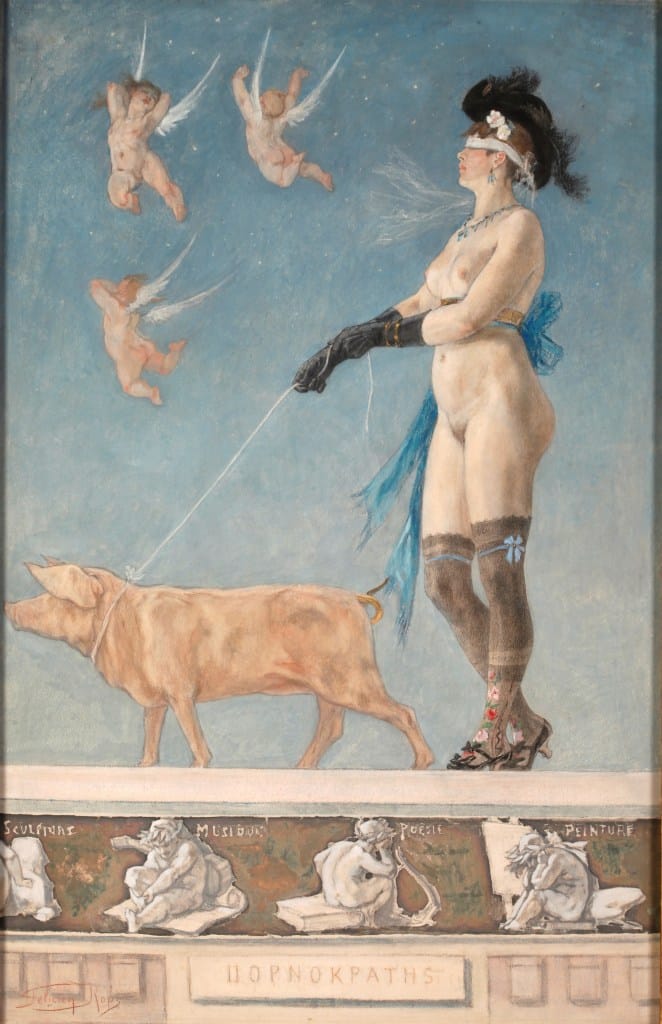

Growth in both population and quality of life brought with it new temptations. More people meant a greater possibility for connection which placed a strain on relationships, complicating the concept of love and its role in marriage. This added complexity along with an increasing capacity for personal agency also lead many to question religion.

With the foundations of society’s traditional pillars of guidance and morality growing weaker by the day, people were left to find their own meaning in life or be left with none at all. For some, this void was filled with materialism. In place of god, decadence became the focus of their worship. The symbolists, however, wanted to find a deeper truth and looked to the occult and mysticism for answers.

While the term Symbolism is used in reference to the overarching movement as a whole, there were some important distinctions between the writers and visual artists involved. Primarily, there was a stronger sense of unity amongst the writers, who shared not only similar motivations but employed similar techniques.

The Symbolists who practiced visual arts were connected in a much looser manner. For them, rather than a distinctive set of rules, techniques, or particular aesthetic approach, Symbolism marked a more general shift in subject matter from that of Realism to something more intimate and personal. Much of what united the Symbolists as visual artists actually took place before they even approached the canvas.

It was through the selection of symbols that they could communicate abstract ideas alongside their personal-held beliefs in a manner that more concrete, definite depictions would not allow. The symbols chosen and the manner in which they were depicted varied greatly between each artist. As a result, the visual component of the movement appears much less unified.

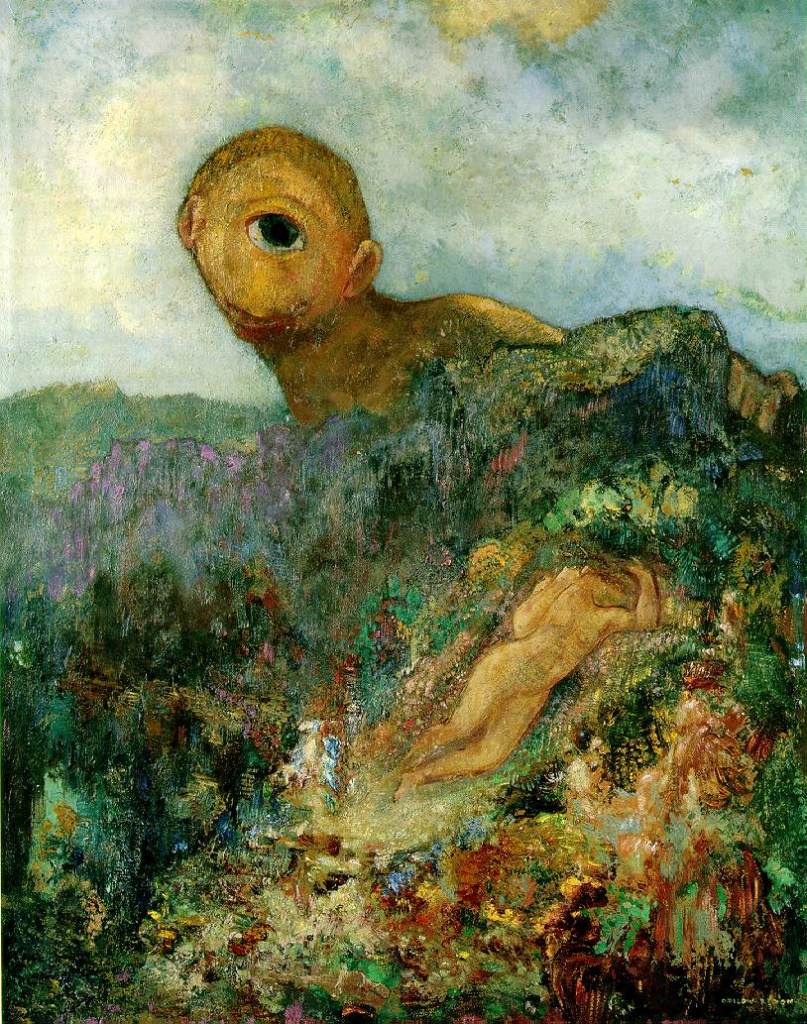

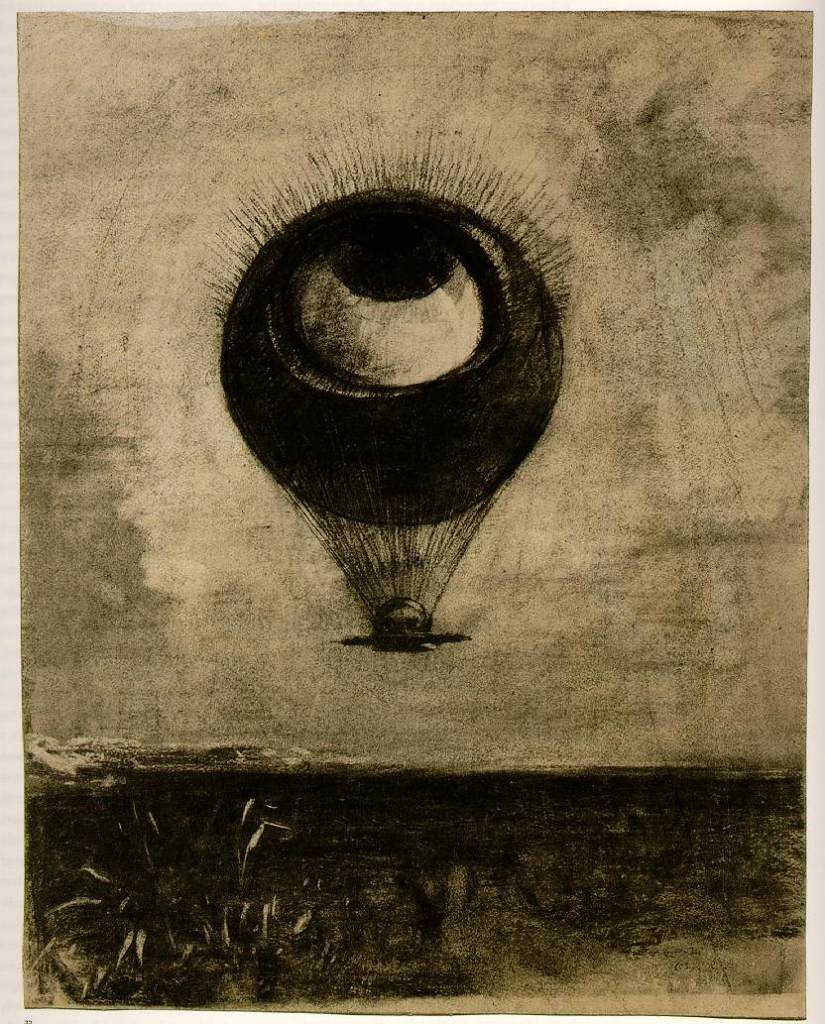

They were, however, unified in their aim. Spurred onward by their desire to escape the general moral decline and decadence of the period, the Symbolists sought to craft new realities—realities full of deeper meanings and connections that reflected their ideals. They believed ultimate truth to be something that could only be found within, and thus, set to work mining their dreams and personal experiences for imagery to inform their work.

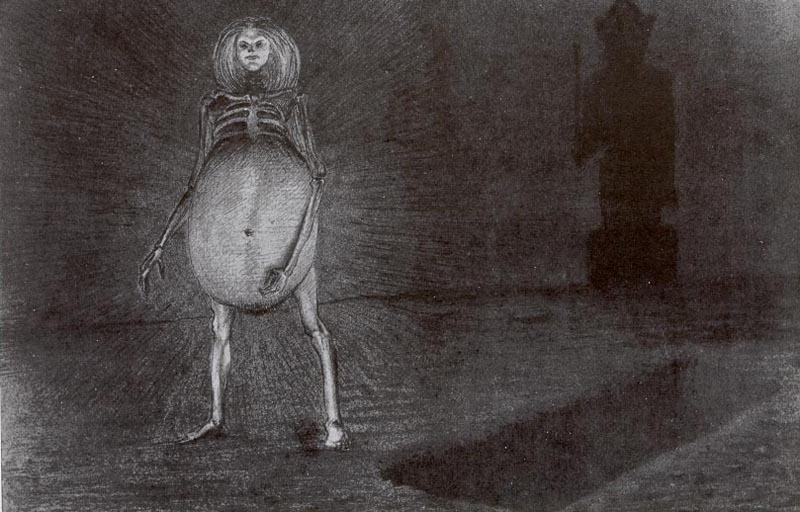

This approach resulted in paintings of a highly personal nature, the meanings of which could not be readily interpreted by audiences. Unlike the symbols found in iconography, which often referenced history and religion, the symbols employed by the Symbolists were much more ambiguous in their meaning. References were at times obscure, and while the objects themselves may have been recognizable, their role or reason for inclusion was not.

This gave the paintings a familiar yet distant, dreamlike quality, shrouding the paintings in an air of mystery. This otherworldly feeling was amplified by the inclusion of references to mysticism and the occult. As the movement was largely a form of escapism, freedom of expression was of paramount importance. Unlike the subject matters found in Realism, which sought to honestly depict life, warts and all, Symbolism provided a place for refuge from the outside world. On the canvas, the artist could explore different ideas and contemplate life’s deeper meanings.

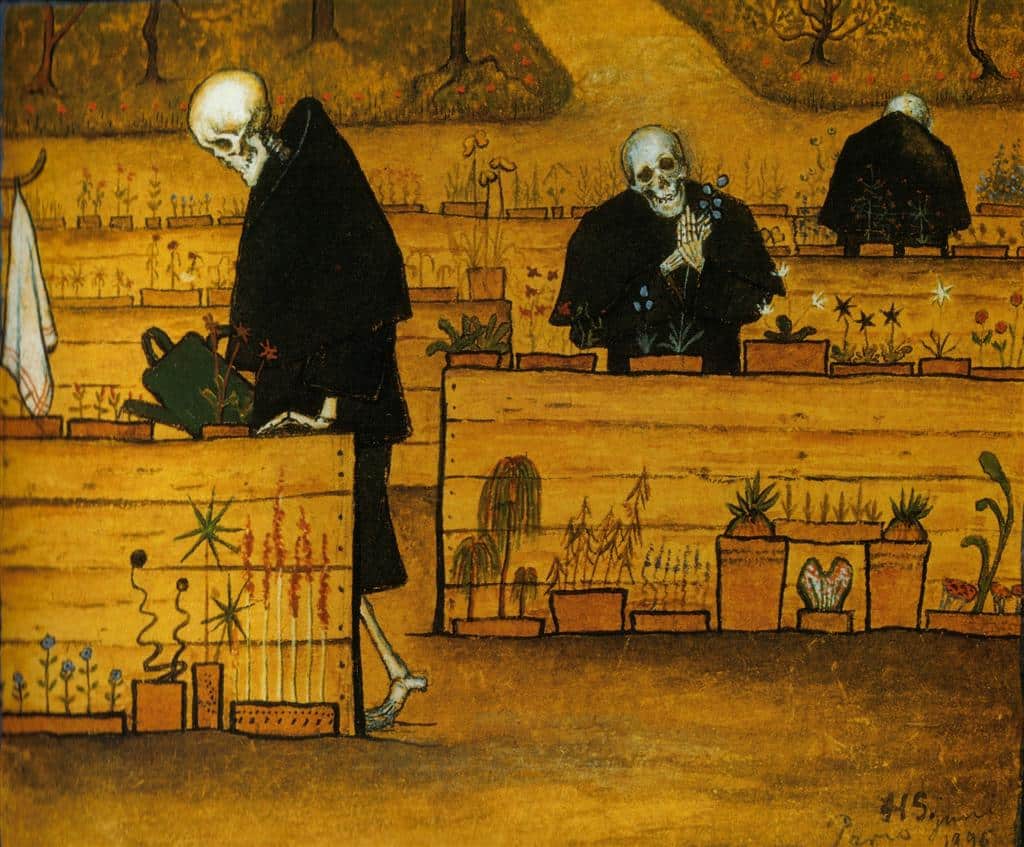

For the Symbolists, this pursuit of a deeper truth often led them to explore the darker, more taboo aspects of humanity. Mortality and eroticism were common topics of exploration amongst the Symbolists, with supernatural figures like angels and chimeras alongside depictions of death and the femme fatale making frequent appearances in their works.

Symbolism would spread and morph over the years, enjoying brief revivals as it moved throughout Europe. Significant practitioners like Jan Toorop, Giovanni Segantini, and Arnold Böcklin, would crop up through the movement’s various iterations in countries like Switzerland, Italy, Russia, and beyond. As is always the case, the movement would eventually fall out of favor as artists grew tired of its obscurities and looked to once again depict life in a raw manner in the years leading up to World War I.

Taylor is a concept artist, graphic designer, illustrator, and Design Lead at Weirdsleep, a channel for visual identity and social media content. Read more articles by Taylor.

ENROLL IN AN ONLINE PROGRAM AT SESSIONS COLLEGE: