Design Deconstructed: Constructivism

Design Deconstructed examines which art movements influenced today’s visual culture, and why.

In the early part of the 20th century, a radical change in the mindset of European artists took place. Beginning in Italy in 1909, on the tails of the Art Nouveau movement, a new school of thought began to emerge. Unlike those before them who had trouble adjusting to their new urban environments and romanticized a return to nature, this new group, the Futurists, as they would come to be called, chose to fully embrace industry and celebrate man’s triumph over nature.

The ideas of Futurism quickly spread through Europe, eventually finding a home in Russia. Here, however, the movement took on a life of its own, going so far as to sever ties with some its Italian forefathers, though the basic tenets of the movement remained the same. Like their Italian counterparts, the Russian Futurists rejected the establishment and classical art.

Looking only to the future, they began to worship the vehicles and mechanisms that would bring them there. Through their art, they sought to channel speed, youth, and violence. Cubism and its machine-like geometry had a large influence on the aesthetic of the movement.

Futurism was also Nationalist in nature. Both the Italian and Russian Futurists celebrated their nation’s industrial accomplishments and saw industry as a means of imparting social influence. In fact, the futurists in Italy longed so much for modernization, that they would go on to form a political party. The Futurist political party, founded by Marinetti, espoused fascist ideals and would later become part of the National Fascist Party, led by Mussolini.

Meanwhile, in Russia, Futurism was morphing into something new. The Russian avant-garde art scene, of which Futurism was a part, had given birth to a variety of new aesthetics and schools of thought. Pulling influence from the general zeitgeist of this period and more specifically Russian Futurism and Suprematism, a new movement was born.

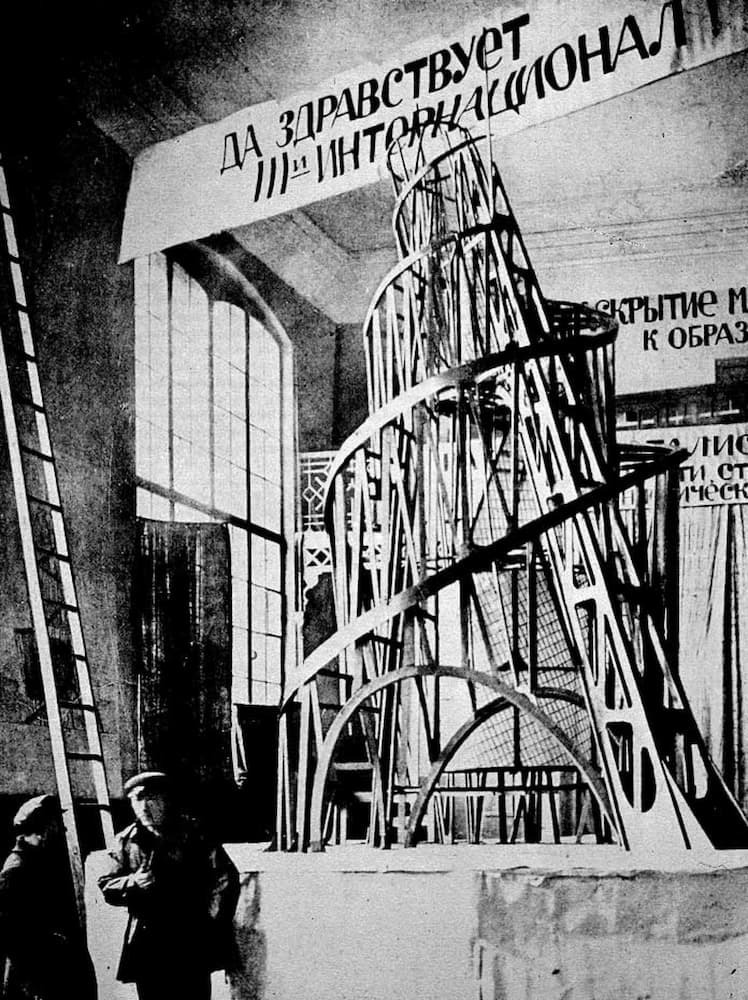

Constructivism, like Futurism, concerned itself with industry, but unlike its forefather, rather than celebrating speed and violence, Constructivism was a movement firmly rooted in technical analysis. Instead of using materials in transformative and decorative ways, Constructivists sought to use materials in a way that was honest to their inherent properties and suitable for mass production.

In 1917, 2 revolutions would take place in Russia. The February Revolution, which would bring an end to Tsarism and result in a provisional government, and the October Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks seized power from said provisional government, would eventually lead to the formation of the Soviet Union.

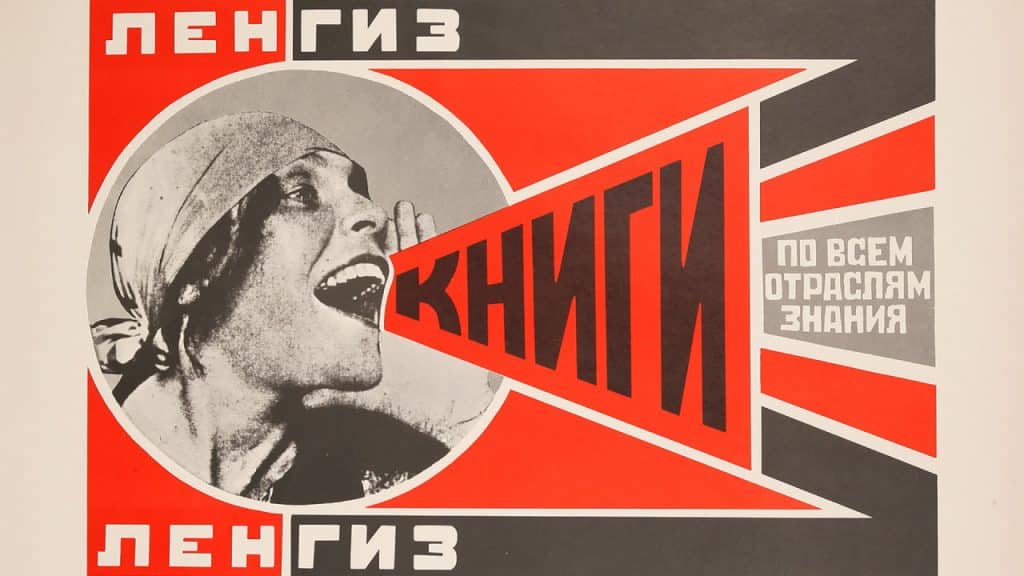

The Constructivists, who saw themselves as constructors of culture, lent their services in support of the Bolshevik government in the form of propaganda and architecture. Their ideology was in fact already in close alignment with the ideals of the party. They viewed art not as a means of self-expression, but rather as a tool in service of society, granting them an important role in the creation of a new culture.

Eventually, the Bolshevik regime would change its opinion of avant-garde art, declaring Socialist Realism the official style of the Soviet Union. Without the freedom to continue, Constructivism, as it was known, would disappear, though its legacy would not. Constructivist practitioners who had expatriated to western Europe would play pivotal roles in the development of the International Style, or De Stijl, and the Bauhaus.

Though Constructivism bears an unfortunate connection to a period of history many would like to forget, the byproducts of this movement won’t soon be forgotten. Like many of history’s tragedies, this period gave birth to insights that would undergo a metamorphosis into something new and beautiful. Constructivism presented a way of thinking that would in turn inspire some of history’s most celebrated designs.

Taylor is a concept artist, graphic designer, illustrator, and Design Lead at Weirdsleep, a channel for visual identity and social media content. Read more articles by Taylor.

ENROLL IN AN ONLINE PROGRAM AT SESSIONS COLLEGE: