Graphic Giants: Bruno Munari

In our Designer Profiles series, we profile groundbreaking 20th century designers who shaped today’s design industry.

Compared to some of his fellow countrymen, like Massimo Vignelli, who made it big in the design world stateside, Bruno Munari may be lesser known outside of his home country of Italy, but his impact upon the arts extends far beyond the limits of the world’s favorite boot-shaped land mass.

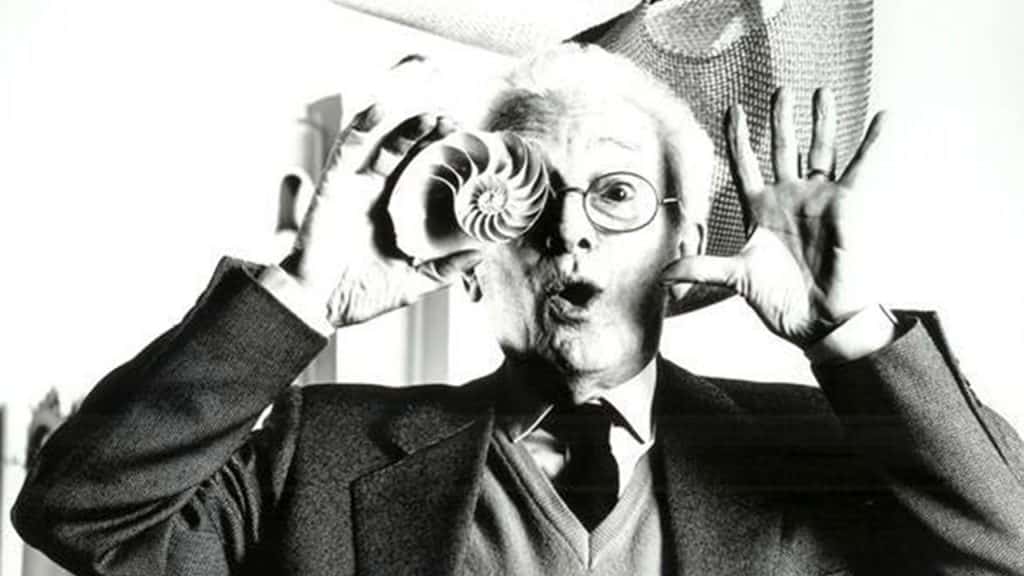

A painter, sculptor, designer, author, TV host, and inventor, Bruno Munari was a generalist in the truest sense of the word, following his creative impulse wherever it led.

Munari was born in 1907 in Milan, Italy, right before a new wave of Italian artists, led by Filippo Tomasso Marinetti and united under the banner of Futurism, would fully embrace the dynamism of industrial city life along with the speed, violence, and technological innovations that came along with it. While Munari’s family headed west to the town of Badia Polesine, the multifaceted practitioners of Italian Futurism continued to expand their thinking and gradually developed their distinctive style.

As the movement began to find its footing in the world of painting, interest in its striking visual aesthetic grew as well, culminating in the movement’s first international exhibition in Paris in 1912. A mere 2 years later though, due to fractures within the group and the start of the first world war, the movement had reached its natural conclusion.

When Munari’s interest in engineering brought him back to Milan in 1925 to work alongside his uncle, he was introduced to the previously defunct but newly reborn Futurism, via its revival once again led by Marinetti. Munari became involved with the movement, becoming friends with the practitioners of the second wave, and displayed his work in several of the group’s exhibitions.

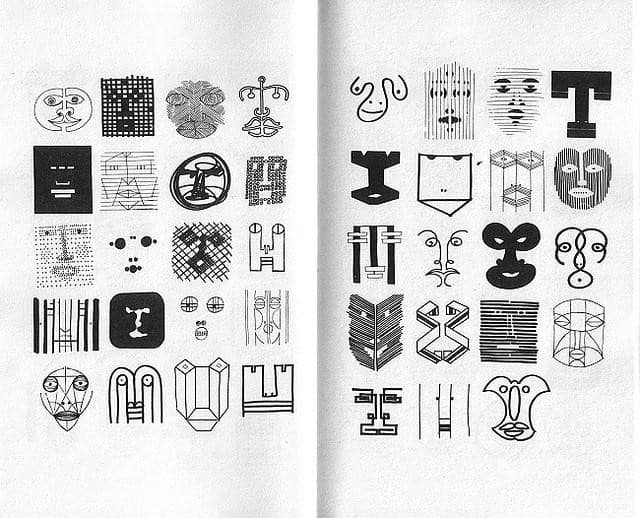

In 1929, Munari began his graphic design studio where he worked with his partner Riccardo Castagnedi. During this period, his contributions to the Futurist movement assumed the form of collage, which featured bold typography and imagery of machinery and urban architecture. Following collage, the next realm Munari’s experiments would lead him to would be sculpture.

This began the period of Munari’s “useless machines”. Consisting of humble materials like cardboard, these initial ventures into abstract sculpture incorporated floating geometric forms, suspended by wire. Whereas previous sculptures under the umbrella of Futurism attempted to communicate movement via the forms themselves, Munari took a different approach, incorporating movement in a literal sense.

Munari’s useless machines were well received by the movement, leading to further exhibitions and job opportunities. The useless machines were so popular in fact, that Munari was able to publish a book with one of Italy’s most prestigious publishers, Einaudi. This further exposure to the world of publishing led to several other art director and graphic consultant roles for magazines such as Domus, Grazia, Il Tempo, and Epoca.

Munari continued to explore movement in his work through kinetic sculpture and photography. Alongside the other founding members of the Movimento Arte Concreta, Munari experimented with motorized and organic movement, creating sculptural works of art that changed with time. Within the realm of photography, Munari began a series of original xerographies which he created using a photocopier by manipulating the position of the subject matter while it was being scanned, resulting in one of one original prints.

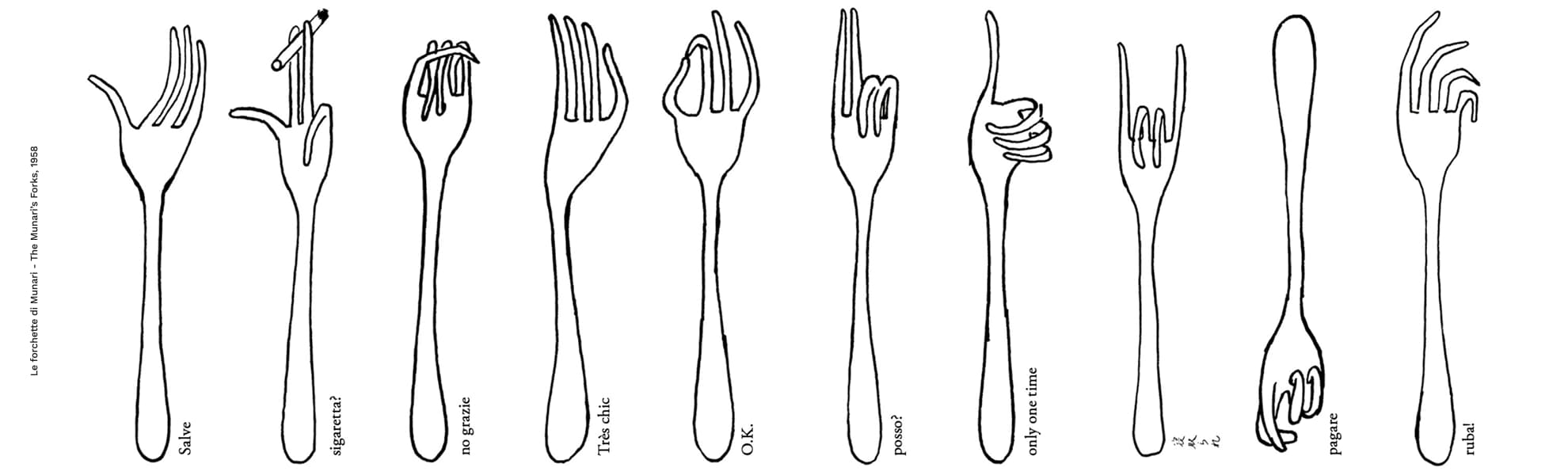

In 1957, Munari began a working relationship with the Italian company Danese, collaborating on a wide array of home goods and objects. Perhaps the most famous object resulting from this partnership is the Cubo ashtray (above), which, thanks to the company’s belief in the genius of Munari’s design, which hides the unsightly ashes, can still be purchased today, despite its initial failure. This CIMA exhibition highlights the playful diversity of his work.

Munari also had a passion for teaching and spreading his creative way of looking at the world. In addition to lecturing at schools like Harvard, Munari also wrote a number of children’s books and developed workshops aimed at inspiring a sense of curiosity in the next generation.

Taylor is a concept artist, graphic designer, illustrator, and Design Lead at Weirdsleep, a channel for visual identity and social media content. Read more articles by Taylor.

ENROLL IN AN ONLINE PROGRAM AT SESSIONS COLLEGE: