Inspiration or Imitation: Striking a Balance

Creative business tips to kickstart your career as an artist, designer, or content creator.

People seem to have a fundamental misunderstanding about creativity. They have this romantic notion that it comes from within. That it’s some sort of mystical process that only a select few of us are capable of tapping into. There may be some truth to that. Sometimes the solution to a problem appears out of seemingly nowhere, coming to us while we’re out on a walk or doing the dishes.

But I think if we were to really try, we could trace that idea back to its source. In the days leading up to the revelation, there was likely something we saw on TV or online that planted the seeds, we only needed time for them to germinate in the fertile soils of our mind before they took root and sprouted into something new.

To others, and admittedly, ourselves, the process can feel mysterious. The source of these seeds isn’t always immediately apparent and once they bear fruit, there’s no time or need to closely examine their roots. But while the exact mechanics of this process remain a mystery, what it really boils down to is that in order to create, we need input.

Those prominent historical figures credited with advancements in language, math, and science, were able to do so thanks to the work of those who came before them. Our advancement as a species is predicated on how we interface with the world around us so it should come as no surprise that the same should apply to our creative endeavors as well. We build on what came before.

The operative word, of course, being build. Imagine if rather than creating the songs that helped to shape the 60’s and beyond, the Beatles had only made covers of songs that already existed. Creativity is about self-expression. It’s natural to want to capture energy from the things that inspire you, but if you’re simply regurgitating what’s already been done, then you aren’t saying much of anything at all.

The act of consuming and digesting the work of our forefathers is part of the process, but it isn’t the final step. Just the easiest. It’s where things go from there, the actual building, where many seem to run into trouble.

But it’s this last part of the equation that is the most crucial, and without it, it’s a bit like taking someone else’s self-portrait and signing it with your name. As a society, we’re taught from a young age to dislike not only the theft of property, but the theft of ideas as well. Whether calling out copycats in preadolescence or ostracizing posers in our teens, the development of our fraud radar begins early on and by the time we’re adults, our sense for inauthenticity is well-honed. With everyone having undergone this same process, its effects are wide-reaching.

The stigma around copying pervades just about every facet of culture. Whether in fashion, product design, or the media we consume, we loathe a fraud. Ours is a culture that values individuality and ingenuity. When these things are falsified, we take offense. Thanks to the internet, this effect has only been heightened. Because the internet has made it so that we all have access to the same information, no reference is secret. If something has been copied, someone will notice.

When something gives off even just the slightest hint of inauthenticity, it’s only a matter of time before one of the internet’s many prolific detectives takes it upon themselves to unearth the truth. And once you’ve been found out, “copycat” is a hard label to shake.

Whether it’s an art critic lambasting Damien Hirst for his uninspired Francis Bacon impression or Instagram accounts like Diet Prada exposing Virgil Abloh for borrowing a bit more than 3% of his reference material, you don’t need to look far to find examples of the public shaming of copycats.

I believe part of this phenomenon has to do with our inherent love for the underdog paired with a strong, historically underserved, sense of justice. We like to see the little guy win. But for the most part, that story was relegated to the big screen. Up until recently, large labels and famous creatives had grown accustomed to “borrowing” ideas with little in the way of blowback.

But now, the internet has provided the voiceless a means of satisfying their craving for justice, a freedom they happily exercise to the fullest. While things on the legal side still have a ways to go, at least we can all dogpile the perpetrators online in the meantime.

But what becomes of those accused of intellectual thievery? Virgil Abloh is an interesting example because at varying points in time and depending on who you ask, he has occupied roles of both the underdog and copycat. For many, he represents the changing face of fashion.

He is a pioneer who managed to successfully break down conventions and carve out a place for himself in a world many didn’t think he belonged. But now, having been caught plagiarising designs multiple times, in some cases from smaller, lesser-known designers, others view him as little more than a smooth-talking fraud.

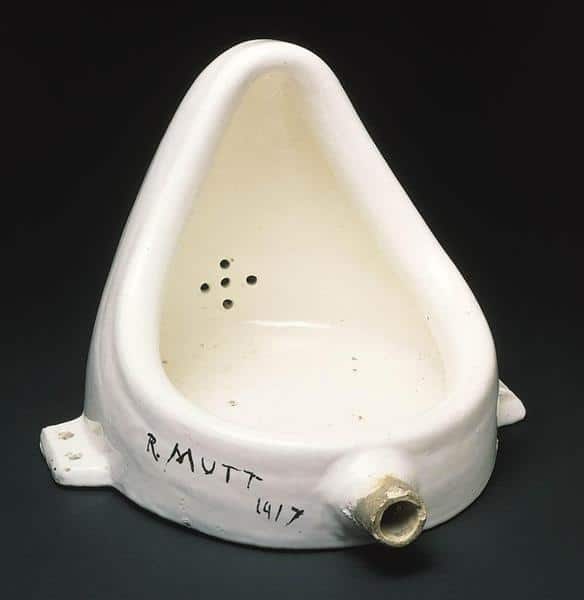

Virgil cites the readymade works of Marcel Duchamp and the use of sampling in hip hop as the inspiration for the core tenets of his design philosophy. Duchamp challenged the art world by reframing the way we look at an object. By taking already existing objects and transplanting them into the context of an exhibition or gallery, he created a juxtaposition that highlighted the transformative effects environmental context can have on our perception.

The key to Duchamp’s success was that he took objects that were neither intended to be nor considered as art and asked the audience to reconsider them.

This key distinction is where Virgil falls short. Inspiration can come from anywhere, but imitation is always linear. Whereas Marcel looked to non-art for his pieces, Virgil never seems to leave the bounds of whatever discipline he’s “working” in. Whether creating furniture, graphics, or clothing, he doesn’t seem to look any further than the work of his peers, adding little more to the original design than a couple of quotation marks.

It isn’t that copying is inherently bad. What it really comes down to is intent. Copying the ideas of others with the intent of passing them off as your own is indefensible. But copying the ideas of others for the sake of understanding them is something else entirely. There are certain insights that can only be gained through the act of copying. But the process shouldn’t end there.

Say your goal is to create a chocolate chip cookie recipe. If the entirety of your process consists of going to estate sales and finding old, handwritten recipes and selecting the most delicious to pass off as your own on your baking blog, don’t be surprised if books start flying from your shelves. You’ve brought that haunting upon yourself. If instead, you treat the process as a study, trying a handful of recipes, experimenting with variations, and comparing the nuances between them, you might be able to deduce an insight you couldn’t have gleaned from one recipe alone.

From here you can place your own spin on this knowledge to make something new while building upon the work before you. This is copying used effectively. The best part is, when done effectively, it leaves no trace. You’ve covered your tracks.

Copying is one of the best tools for learning we have at our disposal. It’s impossible to take a painting lesson from Monet, but one might learn a surprising amount about his process and way of thinking by recreating one of his works. If we’re learning an instrument we don’t jump straight into composing our own songs, we first learn to play the songs of others. Imagine how long it would take to learn to cook if you didn’t have reliable recipes to guide your growth.

By copying the successes of those further along, we’re provided with an immediate form of feedback. We’re able to see when we’ve done something wrong and can adjust accordingly.

Just as while growing up we tried many different forms while developing our sense of self, we do the same while developing our creative selves as well. We try on many different styles before we arrive at something that truly speaks to and for us. In the beginning, when the ingredients are sparse, it’s normal for their influence on our work to be more apparent. As we grow and are exposed to more, we expand our creative vocabulary and begin to build a foundation of our own. The once noticeable influences of our early work have been boiled down into something new. They no longer serve as the main ingredient, but more as seasoning, only detectable by the most discerning of palettes.

“Good artists copy, great artists steal.” Everybody has heard this one before. When caught red-handed, people love to quote Picasso as a means of justifying their actions, but they’re really missing the point entirely. A thief can only be considered successful when their actions go unnoticed. If the source you’ve copied is plain to see, then you’re not a very good thief. Sometimes though it can be hard to tell who’s copied who.

This tends to be the case when we find ourselves in the midst of a trend. The current landscape of corporate logos and web design being a good example. It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly where the move towards the minimalistic logo treatment began but here we are in 2021, with companies looking more and more the same every day. If copying gives birth to a trend, then, in contrast, inspiration gives birth to a movement. Had the key figures in any movement simply copied one another, there would have been no room for growth, and that’s what this is all really about anyway. Growth.

What begins as imitation grows into inspiration and the cycle continues. Gradually, the more we learn, the more we demystify the process. We realize there never really was a secret to begin with, we just lacked the skills and understanding to properly frame what we were seeing. It’s through copying the works of our idols that we discover their creators didn’t possess any secret knowledge, any inherent ability that made their level unattainable.

The creative process isn’t magical, we’re simply building on what has come before, just as those before us did. But that doesn’t mean you can’t play coy the next time someone asks how you come up with your incredible ideas. After all, who doesn’t want to feel magical?

Taylor is a concept artist, graphic designer, illustrator, and Design Lead at Weirdsleep, a channel for visual identity and social media content. Read more articles by Taylor.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SESSIONS NEWS:

ENROLL IN AN ONLINE PROGRAM AT SESSIONS COLLEGE: