Why They Work: Alphonse Mucha

Our Why They Work series explores what makes a leading artist unique.

Alphonse Mucha was a Czech artist whose name is synonymous with the Art Nouveau movement. His work and the style he developed during the period of 1893 to 1903 came to define an era and forever serve as an influence to future illustrators. However, Mucha’s journey to reach that point was a struggle and the fame he achieved in his thirties was a far cry from the conditions he found himself in just a few years prior.

Mucha was born in the Czech Republic where at a young age he discovered a penchant for drawing. After being rejected by the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, he managed to find work painting scenery for theatrical productions in Vienna.

Through a series of chance encounters and happy accidents, he came to meet Count Eduard Khuen Belasi, a wealthy patron of the arts who would forever change the course of Mucha’s life. With Belasi’s financial support, Mucha was able to attend the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, and later moved to Paris in the autumn of 1887 to pursue a traditional atelier education at the Académie Julian.

The conditions of his financial support required that he send regular updates to the count regarding his painting progression and when school finished for the summer, he would return to the Count’s castle to paint wall murals. After 2 years of this, upon an unexpected late return to Paris, Mucha decided on a change of direction. He chose to enroll in classes at a different atelier, Académie Colarossi, and found a place for himself in Rue de la Grande Chaumière, located in Paris’ Latin Quarter, where he would live for the next 25 years.

Within months of settling into his new arrangements, Mucha received a letter from the Count stating that his financial backing would cease immediately. The Count felt that Mucha, who was then 29, would be a student forever, and hoped that rescinding his financial backing would give Mucha the push he needed to make a name for himself, though he would not explain this until years later.

Mucha’s life took a sudden 180. He could no longer afford heating or food, let alone his tuition at Académie Colarossi, so he sought out employment as an illustrator. These times proved to be tough but he was able to find enough illustration work to survive.

Through a friend from Académie Colarossi, Mucha came to meet Madame Charlotte, whose café served as a center for the area’s developing art scene. Its location across from the atelier meant that there was a constant influx of both students and instructors from the school. After finding a studio apartment above the café, Mucha spent every day in there, developing a network of contacts and learning of the current trends in art, one of which was Japonism, the influence of which would later become Art Nouveau.

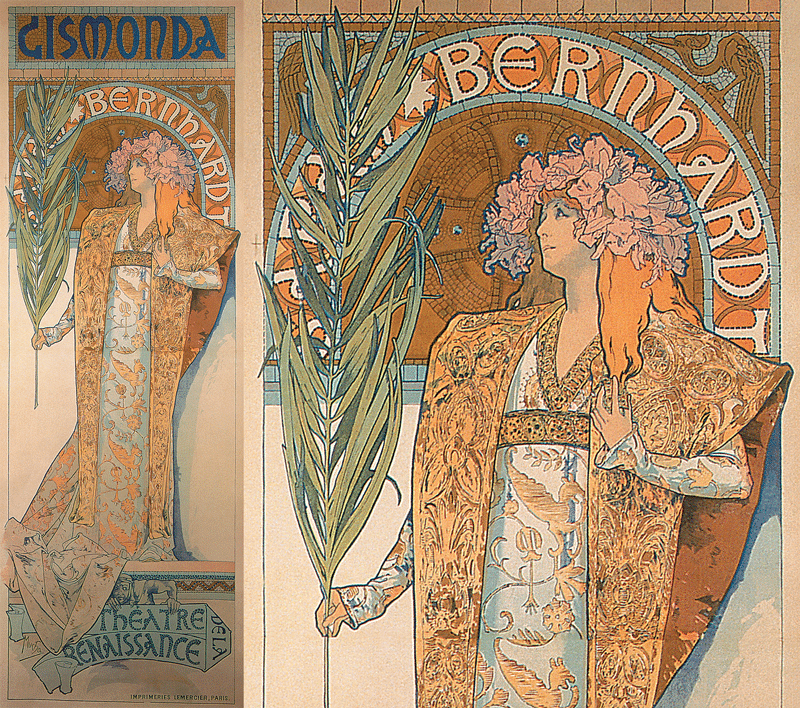

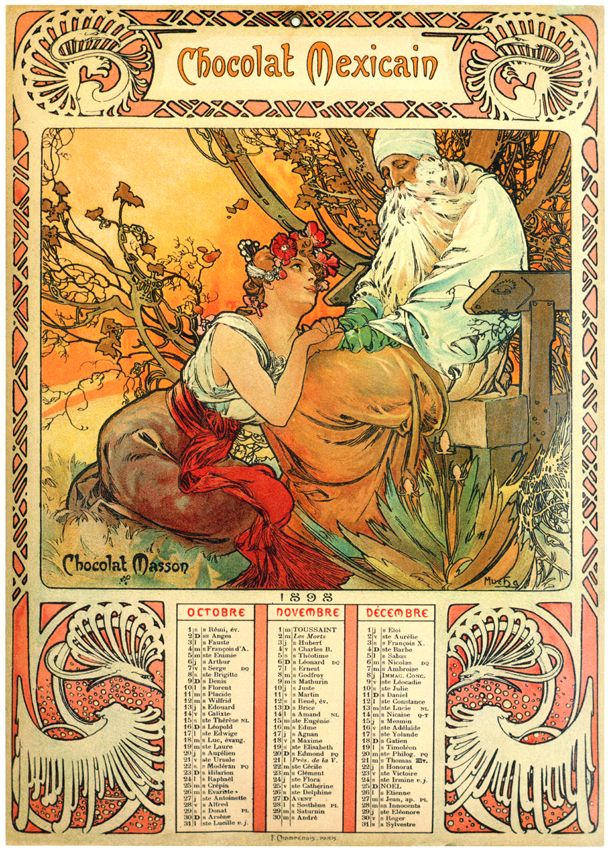

It was through these contacts that he was given the opportunity to illustrate a series of 12 Zodiac illustrations which were to be used for a calendar. These illustrations marked the earliest indications of what would come to be known as “Le Style Mucha” and their commercial success would lead to his commission for a theatrical poster of Sarah Bernhardt as Gismonda, the piece that would launch him into instant fame and solidify his artistic influence on the era.

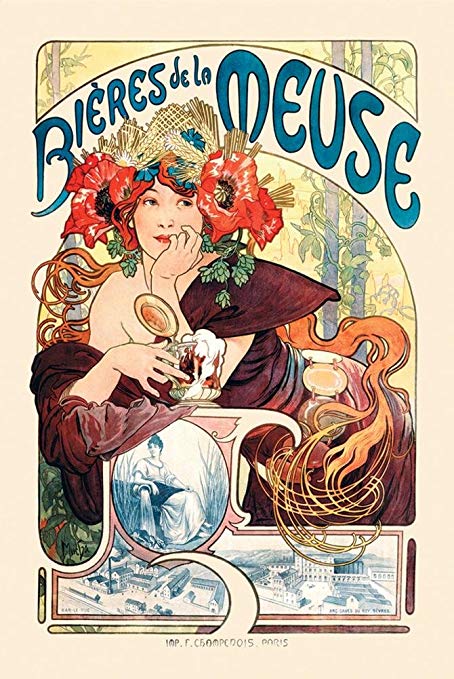

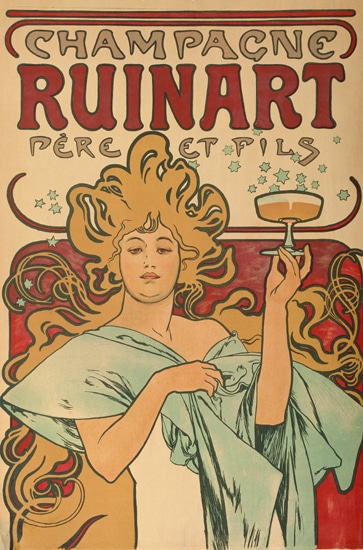

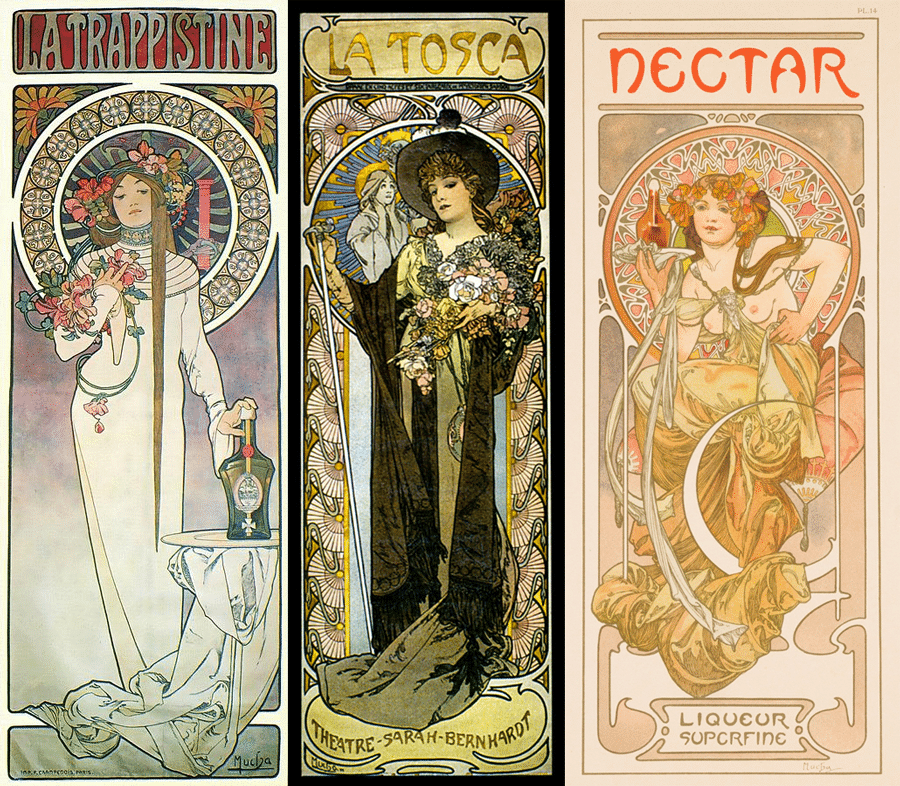

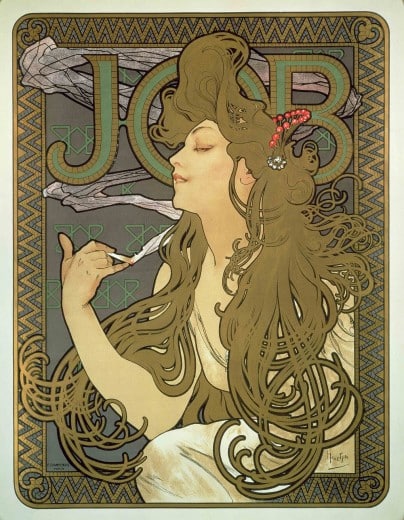

“Le Style Mucha” is extremely distinctive and its obvious graphic appeal continues to inspire artists to this day. His work contained aspects that visually tie him to the Art Nouveau movement of the time, but his boldness of approach was unique to him alone.

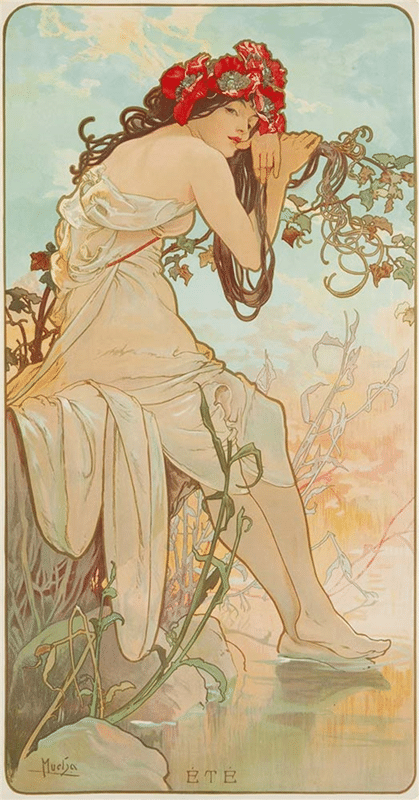

His compositions were often very tall. One of the first instances of this habit was his first poster of Sarah Bernhardt for Gismonda, which bucked the trend of using square posters which was standard at the time. Rather than confining her to a box, he chose to depict her in her full glory, utilizing the composition’s full vertical length to communicate her larger than life on-stage character. These tall compositions became a favorite of Mucha’s and he would often employ them for the rest of his career.

Another distinctive feature of Mucha’s work was his use of line. He made use of bold outlines and finer lines within his shapes to communicate material and paired these oftentimes with simple color fills, leaving the job of communicating value to his lines. The style is very flat and it’s no surprise that some of his biggest modern fans are those working in the comics industry. The shape language he employs in his approach to rendering hair is perhaps what most links him visually to Art Nouveau.

His long flowing lines lend his pieces a sense of movement and call to mind the gentle curve of the stem of a flower or the spray of a crashing wave. Mucha’s work is also highly decorative. Like the other Art Nouveau artists, his pieces often feature ornamentation consisting of objects from nature, like flowers, stars, and birds.

Though Mucha’s attempts to re-establish himself as a fine artist in the latter part of his career proved unfruitful, it’s hard to blame the world for asking for more of the same from him. The work he created during his time in Paris is as awe-inspiring today as it was when it was created.

The timeless appeal of his work has rightfully earned him a place as one of the most important illustrators of all time, and that… is why they work.

Taylor is a concept artist, graphic designer, illustrator, and Design Lead at Weirdsleep, a channel for visual identity and social media content. Read more articles by Taylor.

ENROLL IN AN ONLINE PROGRAM AT SESSIONS COLLEGE: