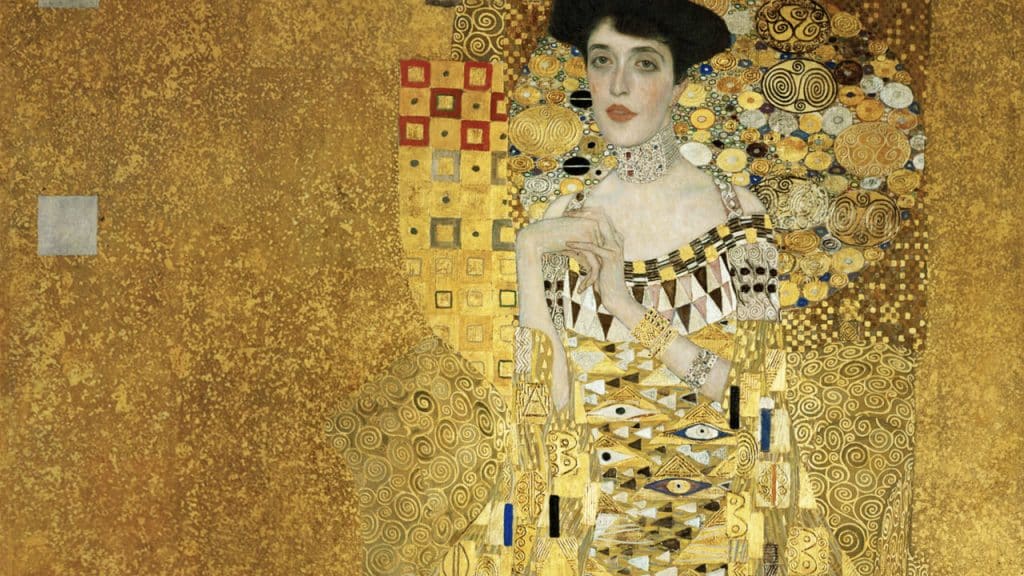

Why They Work: Gustav Klimt

Our Why They Work series explores what makes a famous artist unique.

Gustav Klimt was an Austrian painter who today is mostly associated with the Art Nouveau movement. He was born to a Bohemian father who worked as a gold engraver and a mother who was an opera singer. His parents’ vocations would later have a profound impact on his art. He was the second of seven children and had a brother who was also a painter. In 1876, he began his education at the School of Arts and Crafts at the Museum of Art and Industry in Vienna.

During his seven years spent at the school, he studied metalworking, mosaics, and art history. It was during this time that he built the extensive visual vocabulary of motifs that would later inform his decorative approach to painting. At this point in time, historicism was in vogue and Klimt’s early works reflected this. Upon leaving school he began a career decorating public buildings alongside his brother and Franz Matsch, whom he met in school.

The three worked as a team and stylistically, they had the same academic realism of their contemporaries, though Klimt’s scientific attention to detail would push him into a leadership role. In the beginning, their work mainly consisted of theaters, and through their successes would later move on to paint castles and museums. The three would go on to receive a commission for the Kunsthistorisches, a newly built museum.

It was during this commission that Klimt would first begin to develop the Symbolist ideas and the flat decorative approach that would later inform his works during the Art Nouveau era.

Following the death of his brother in 1892, Klimt’s world was drastically altered. He descended into depression, putting a pause on his painting career for the next three years. Upon emerging from this dark mental place, he and his work had transformed completely, and the style he is most known for today began to take form.

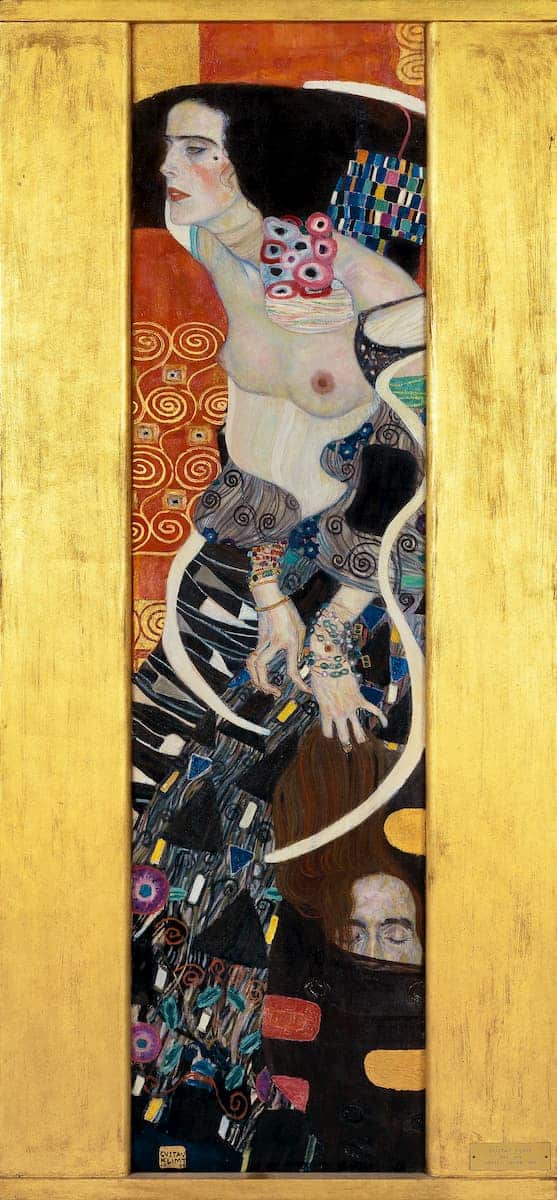

It would appear that the years spent recreating historic styles had firmly planted their roots within Klimt, as he would never fully shake their influence. The motifs and symbols he studied from Greek and Egyptian history would make frequent appearances in his work, slowly melting together and morphing into his own distinctive style of decoration. His own Slavic history was also prominently featured throughout his career, with references made to symbols from folklore.

Another important stage in the evolution of Klimt’s style coincided with the Vienna Secession, which marked a cultural shift in taste from the academic historicism Klimt had worked in previously. It was during this period that Klimt began to explore composition and theme, taking his work in an entirely new direction. Gone were the days of historical depictions and allegory. Viennese art culture had stepped into a new era and naturally, they were met with some resistance.

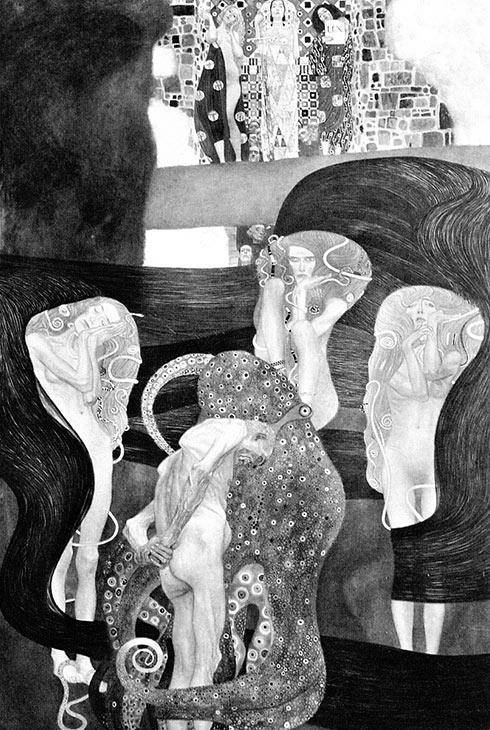

At this point, Klimt had been commissioned for three paintings to hang on the ceiling of the Great Hall at the University of Vienna, where both the architectural style and surrounding works remained firmly in the academic historicism style. In 1900, he debuted the first of the three paintings, Philosophy. Its loose, poetic composition and blending of styles stood in harsh contrast to its intended environment. The piece received heavy criticism from local academia, though it would go on to win a gold medal at the Paris Exposition.

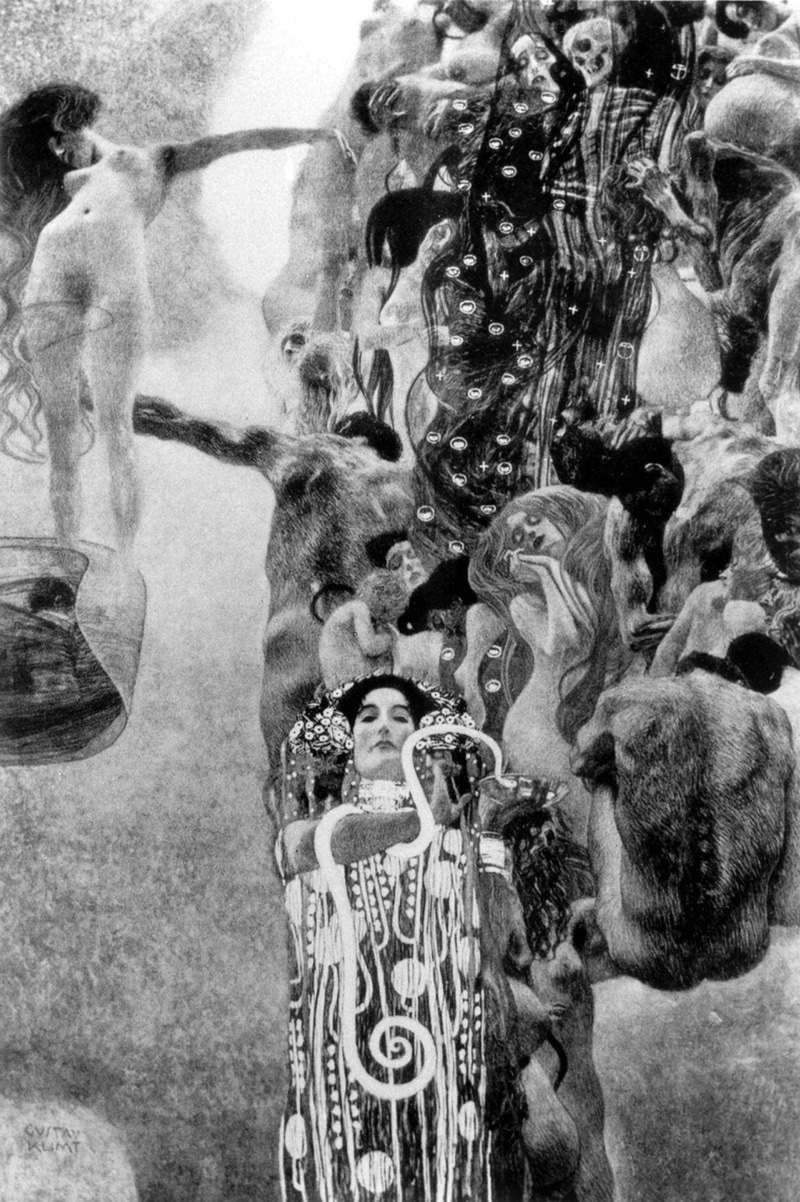

His next painting, Medicine, depicted an amorphous mass of bodies in various stages of life, huddled together to form a whole. A woman and her child appear to be being pulled simultaneously toward and away from the group, within which, death is lurking, gazing in their direction. At the foot of the group stands Hygieia, the Greek goddess of healing. Dressed in decorative garb, she holds a small bowl into which a golden serpent contorts its body around her arm to enter. Like Philosophy, Medicine was labeled as immoral and its debut caused an uproar among Viennese press and academia.

However, in an early example of the Streisand effect, the negative press had the opposite of the intended effect. Rather than shun the work into obscurity, the public rushed to see the scandalous new painting.

Perhaps emboldened by the response to Medicine, Klimt doubled down to create an even larger deviation in style for the 3rd and final painting, Jurisprudence. Upon its completion in 1903, the Ministerial Commission retracted the set’s placement in the Great Hall. Klimt would later reacquire his paintings in 1905, but the event would mark the end of his government-commissioned work and cement his resolve toward his new direction.

Klimt was rebellious. By deviating from what was expected of him, he challenged the status quo and planted his flag firmly amongst the Secession. He was also far ahead of his time. He longed to merge architecture and painting so as to create a non-elitist art for all to enjoy. His ambitions are echoed in today’s street art.

Today, Klimt is admired not only for the beauty of his paintings, but also the courage and ingenuity he expressed in their creation, and that… is why they work.

Taylor is a concept artist, graphic designer, illustrator, and Design Lead at Weirdsleep, a channel for visual identity and social media content. Read more articles by Taylor.

ENROLL IN AN ONLINE PROGRAM AT SESSIONS COLLEGE: